Blog: an alternative Nobel reading list

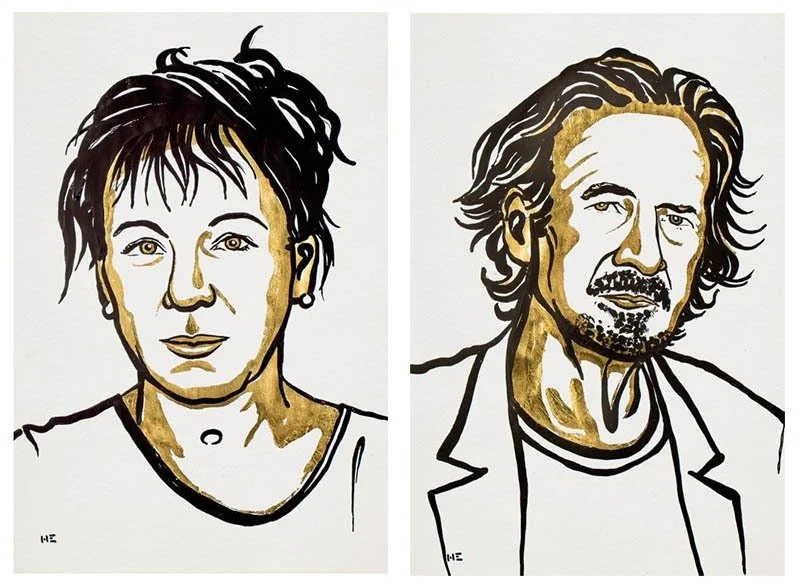

Olga Tokarczuk and Peter Handke

Opinion by Michael Halmshaw, Digital Manager

Earlier this month, the Irish author John Banville received a call telling him he was one of two winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature. Banville called friends and family to deliver the news, only to discover, less than an hour later, that the call had been a hoax. As it so happened, Banville would have failed to meet the criteria for the Nobel Committee for Literature's new mandate, as they searched for a 'global totality,' which moved away from the tone of prior selections. 'Prizes,' Banville reflected, 'appeal to the child within.'

Anders Olsson, chair of the Nobel Committee for Literature, stressed earlier this year the organisation's commitment to change, emphasising that 'previously [the Committee] had a more Eurocentric perspective' which was 'much more male-oriented.'

The Committee initially delivered on its latter assurance, awarding the 2018 Prize to Polish author Olga Tokarczuk, but lapsed into controversy with the 2019 award, bestowing the world's second richest prize on Austrian novelist and playwright Peter Handke. This is the same Handke whose literary merits are usually cited in advance of raising his track record of public apologias for the former Serbian President Slobodan Milošević, who died in The Hague while on trial for war crimes. Jennifer Clement, PEN International President, issued a statement highlighting the problematic nature of the academy's decision:

to recognise an author who has repeatedly questioned the legitimacy of well-documented war crimes is highly regrettable, particularly as it will, no doubt, be distressing to the many victims.

Aside from Handke's well-documented views, his choice represents a total failure on the part of the academy to meet the assurances – non-male, non-European – they had enumerated merely a week before the award.

Their choice ignited an impassioned discussion at PEN International. If we could make this decision next year, who would deserve the prize? I put the question to our board, who represent the Americas, Asia, Africa, the Middle East and Europe, with the caveat that their choices could not be from Europe. We live in a time when writers can bypass publishers entirely and publish their work to a global audience immediately: why not look further?

Multiple members of the board put forward the multi-award-winning Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o, who wrote the first modern Gikuyu language novel in prison. The board cited 'his work for the discipline of literature,' his 'experimenting with media and style,' and praised him as an author who occupies both 'creative and critical domains.'

There is Melissa Lucashenko, an Australian writer of Goorie (Aboriginal) and European heritage, whose work spans genres, 'a very significant and rising voice on issues of marginalization, silencing and of the resilience of Australian Indigenous culture, including language.'

Several suggestions hailed from Japan. The first was Yoko Ogawa, author of short novels and short stories such as The Diving Pool which blend violence and sexuality in a haunting way. Hideo Kawakami, who has won every major literary prize in Japan, was also put forward. Her Strange Weather in Tokyo, which was shortlisted for the 2013 Man Asian Literary Prize, is a poetic story of solitude and love.

Another multiple vote-getter was David Grossman, a peace activist and recent winner of the International Man Booker Prize for his novel A Horse Walks into a Bar. Grossman writes in an intense and lyrical Hebrew: many of his novels are available in English.

A Francophone colleague proposed the Senegalese novelist Mariètou Mbaye Biléoma, who writes under the pseudonym Ken Bugul; Danny Lafferière, a Haitian-Canadian author occasionally compared to James Baldwin and Henry Miller; and a Nigerian writer who 'although she is young' and writes in English, could one day take the prize – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

Major American writers were suggested in abundance: Margaret Atwood (recently described as ' a real sage' by Jeanette Winterson), Joan Didion, Richard Ford and Marilynne Robinson.

Finally, a couple of board members suggested Salman Rushdie, born in Bombay in 1947 and now holder of UK-US citizenship. Rushdie awarded Peter Handke a runner-up prize of his own 20 years ago, in the category of 'International Moron of the Year.' The winner of said award was pro-firearms campaigner and actor Charlton Heston. Rushdie himself has won many awards, including the Booker of Bookers in 1993.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of its author, and where quoted, the PEN International Board. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of PEN International or its members.